By:

Laura M. Getz

Elizabethtown College, USA

Tomas Chamorro-Premuzic

Goldsmiths, University of London, UK

Michael M. Roy

Elizabethtown College, USA

Karendra Devroop

North-West University, Potchefstroom, South Africa

Abstract

The current study examined the relationship between individual differences in uses of music (i.e. motives for listening to music), music preferences (for different genres), and positive affect (PA) and negative affect (NA), thus linking two areas of past research into a more comprehensive model. A sample of 193 South African adolescents (ages 12–17) completed measures of the above constructs and data were analyzed via correlations and structural equation modeling (SEM). Significant correlations between affect and uses of music were tested using SEM; a model whereby PA influenced background and cognitive uses of music, NA influenced emotional use of music, and higher uses of music led to increased preferences for music styles was supported. Future research for uses of music and music preferences are discussed.

Keywords

adolescents, music preferences, PANAS, South Africa, uses of music.

There is no doubt that music is a ubiquitous force in our daily lives. We are bombarded with music at work, in restaurants, in waiting rooms, and at home on a daily basis. Annual sales

There is no doubt that music is a ubiquitous force in our daily lives. We are bombarded with music at work, in restaurants, in waiting rooms, and at home on a daily basis. Annual sales figures for compact disks, personal music players, and concert attendance climb into the billions each year (International Federation of the Phonographic Industry (IFPI), 2009; Schwartz & Fouts, 2003). This high level of accessibility means that music may be actively used for a variety of reasons in different settings (e.g. North, Hargreaves, & Hargreaves, 2004; Rana & North, 2007). Indeed, past research has shown music to be used for social interaction/identity formation (Rentfrow & Gosling, 2006; Tekman & Hortaçsu, 2002), emotional regulation (Juslin & Laukka, 2003, 2004; Miranda & Claes, 2009; Saarikallio & Erkkilä, 2007), self-actualization (Tarrant, North, & Hargreaves, 2000), cognitive needs (North, Hargreaves & O’Neill, 2000), or simply out of habit (North et al., 2004). The use of music as a social function for identity formation may be even more pronounced in adolescents (Bakagiannis & Tarrant, 2006; North & Hargreaves, 1999; North et al., 2000; Tarrant et al., 2000).

Given this background, it comes as no surprise that psychologists have long taken an interest in individual differences in music usage and preferences (Cattell & Anderson, 1953a; Little & Zuckerman, 1986). In recent years, two main lines of research have emerged relating music to personality: uses of music and music preferences.

Uses of music

Previous research has examined multiple aspects of music usage in everyday life, such as where, when and why people listen to music (North et al., 2004; Rana & North, 2007). Motives for listening to music have been broken down into three major categories by Chamorro-Premuzic and Furnham (2007): manipulation or regulation of emotions (emotional use); rational or intellectual appreciation of music (cognitive use); and music as background to working, studying, socializing or performing other tasks (background use; see also Chamorro-Premuzic, Swami, Furnham, & Maakip, 2009; Chamorro-Premuzic, Gomà-i-Freixanet, Furnham & Muro, 2009). In relation to personality, emotional use of music has been found to positively correlate with neuroticism, explained in terms of higher emotional sensitivity among those high in neuroticism (Costa & McCrae, 1992; Juslin & Laukka, 2003; Juslin & Sloboda, 2001). In addition, background music has been found to positively correlate with extraversion, in line with Eysenck and Eysenck’s (1985) finding that extraverts are under-aroused compared to introverts and thus have a greater tolerance of background stimuli. Finally, cognitive use of music has been shown to positively correlate with openness, explained in terms of higher intellectual curiosity and need for cognition, as well as the positive link between openness and self-estimated and psychometrically measured intelligence (Chamorro-Premuzic & Furnham, 2005).

Music preferences

One of the earliest studies on music preferences was Cattell and Anderson’s (1953a, 1953b) I.P.A.T. Music Preference test, which interpreted preference factors as unconscious reflections of specific personality characteristics. Since then, research has focused on more explicit links between music preferences and personality. For example, Little & Zuckerman (1986) found a positive link between sensation seeking and preference for rock, heavy metal, and punk music, and McCown, Keiser, Mulhearn & Williamson (1997) found a positive correlation between extraversion, psychoticism, and preference for rap and dance music. Rentfrow and Gosling (2003) indicated that musical preferences could be organized from 14 genres into four independent dimensions: Reflective and Complex, Intense and Rebellious, Upbeat and Conventional, and Energetic and Rhythmic. Extensive links were found between each dimension and typical personality traits (see Rentfrow & Gosling, 2003, p. 1248–1249). This study was the first to suggest a ‘clear, robust, and meaningful structure underlying music preferences’ (p. 1250); however, they point out that future research should extend this research to other age groups and cultures in order to validate the present structure.

Present study

While research within these two fields may seem extensive, several important limitations exist in the present body of work. First, previous studies have tended to focus on either uses of music or music preferences in relation to personality, but no studies have combined these fields. The present study is therefore an attempt to unify research on uses of music and music preferences into a more comprehensive model.

Second, only a few studies have focused on non-western cultures (Chamorro-Premuzic, Swami et al., 2009; Rana & North, 2007). While music itself is a universal phenomenon, previous research has suggested that there may be differences in music usage and perception as a function of ethnicity (Eerola, Himberg, Toiviainen & Louhivuori, 2006; Gans, 1974; Gregory & Varney, 1996; Saarikallio, 2008). A cross-cultural approach to music research can help to discover common motives for listening to music as well as culturally specific uses. Therefore, the present study extended uses of music research by studying adolescents in South Africa. Though it is true that South Africa, like many other countries, has been strongly influenced by western cultures, considerable diversity still exists, with White, traditional African, and Southeast Asian ethnic groups represented. Our current study examined a population of African and Southeast Asian participants from the KwaZulu-Natal province that could be categorized as ‘non-Western’ (Eerola et al., 2006 and Eerola, Louhivuori & Lebaka, 2009 use a similar descriptor).

Third, past studies using the Uses of Music inventory have only used university students (Chamorro-Premuzic & Furnham, 2007; Chamorro-Premuzic, Gomà-i-Freixanet et al., 2009), so the present study extended the inventory to the adolescent population. Because most adolescents consider music to be an integral part of their lives (Christenson & Roberts, 1998; Zillmann & Gan, 1997), it is important to understand their motives and preferences for listening to music. Previous research on adolescents’ music usage has shown strong links to socialization, entertainment and background use (Bakagiannis & Tarrant, 2006; North, & Hargreaves, 1999; North et al., 2000; Tarrant et al., 2000), and to coping and emotional regulation (Juslin & Sloboba, 2001; Miranda & Claes, 2009; North et al., 2000; Saarikallio, 2008; Saarikallio & Erkkilä, 2007; Tarrant et al., 2000), with less evidence for intellectual usage of music (Demorest & Serlin, 1997; Eerola et al, 2006; Krumhansl & Keil, 1982; North et al., 2000). It may be that adolescents’ cognitive use of music is lower because they are less capable than their older counterparts of critically analyzing rhythmic and melodic structure (Demorest & Serlin, 1997; Krumhansl & Keil, 1982); additionally, background and emotional uses of music may be used more by adolescents because of the important role music plays in identity formation (North & Hargreaves, 1999; North et al., 2000; Tarrant et al., 2000).

Finally, past research has mainly focused on the Big Five factors of personality as the basis for comparison. In the present study, we examined whether participants’ levels of positive affect (PA) and negative affect (NA), as measured by the PANAS (Watson & Tellegen, 1985; Watson, Clark & Tellegen, 1988), were predictive of their music use. The PANAS uses one-word responses and straightforward vocabulary, which was beneficial because the participants in this study were adolescents (ages 12–17) who were largely unfamiliar with personality scales and testing. Past research (see Lonigan, Hooe, David, & Kistner, 1999) has found the PANAS to be a reliable and valid measure of children’s (age range 9–17) affect, while reports of the Big Five with adolescents show significant age differences in coherence and differentiation of the factors between participants ages 10–20 (Soto, John, Gosling & Potter, 2008). Importantly, state temperament shows reliable links to overall disposition and personality (Costa & McCrae, 1980; Schmukle, Egloff & Burns, 2002; Watson & Clark, 1984). Since PA has been found to be highly correlated with extraversion and openness (DeNeve & Cooper, 1998; Lucas & Fujita, 2000; Mitte & Kämpfe, 2008), we expected that PA would be predictive of higher background and cognitive uses of music, while past positive links between NA and Neuroticism (Costa & McCrae, 1992; DeNeve & Cooper, 1998), would suggest that NA would be predictive of higher emotional use of music (Chamorro-Premuzic & Furnham, 2007, Chamorro-Premuzic, Gomà-i-Freixanet et al., 2009; Chamorro-Premuzic, Swami et al., 2009).

In sum, the current study examined the relationship between PA and NA, uses of music and music styles preferences. This study extended past research in these domains into a more comprehensive model, using a novel age group and culture. Structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to test a model wherein affect (PA and NA) predicts uses of music, which in turn, predict music preferences.

Method

Study site and participants

Pietermaritzburg, founded in 1838, is the capital of the KwaZulu-Natal province of South Africa. It is the second largest city in the province with a population of approximately 750,000 people. The city is a major producer of aluminum, timber and dairy products. Because of mandatory separation during the Apartheid, much inequality still exists among racial groups. Public schools in the KwaZulu-Natal province, catering largely to traditional African and Southeast Asian students, currently lack the resources necessary to provide students with formal musical instruction; therefore, the present study was completed as part of a music intervention service project at two Pietermaritzburg secondary schools.

Participants in the present study included 193 (81 males, 107 females, 5 not reported) secondary school students from Pietermaritzburg, South Africa (age range 12–17, M = 13.77, SD = .85). The sample consisted of 77.2 % traditional Africans, 13.2 % of Southeast Asian descent and 7.4% mixed ethnicity (the remaining participants listed themselves in other ethnic groups). Nearly all of the African participants (84.9%) spoke Zulu at home, while the remaining participants largely spoke English at home (88.4%). As all South African secondary school classes are taught in English, no translations of the scales were used. Despite a lack of formal music education, the majority of participants (75%) reported listening to music on a daily basis and to owning a radio or music playing device (75.6%).

Measures

Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS: Watson & Tellegen, 1985; Watson et al., 1988). This is a 20-item questionnaire measuring current positive and negative temperaments. Items are rated on a five-point scale (1 = Very slightly or not at all; 5 = Extremely), and participants are asked to rate to what extent they ‘feel this way right now, that is, at the present moment’. Watson et al. (1988) report that the scale items are internally consistent and have excellent convergent and discriminant correlations with lengthier measures of the underlying mood factors. In the present study, two items were changed to make the vocabulary more accessible to younger participants (Distressed became Worried, and Jittery became On edge). Cronbach’s a, M and SD for the two subscales (PA, NA) are reported in Table 2.

Uses of Music Inventory (Chamorro-Premuzic & Furnham, 2007). This is a 15-item scale measuring views regarding music, when it is listened to and why. Items are rated on a five-point scale (1 = Strongly disagree, 5 = Strongly agree) and the averages of certain items are computed to arrive at the three subscales of this inventory: Emotional use of music (M[emot], five items; sample item: ‘Listening to music really affects my mood’); Cognitive, intellectual, or rational use of music (M[cog], five items; sample item: ‘I often enjoy analyzing complex musical compositions); and, Background or social uses of music (M[back], five items; sample item: ‘I often enjoy listening to music while I work’).

Because Cronbach’s alphas were low for M[emot] and M[cog] (a = .25 and .23, respectively), principal component analysis (PCA) was performed on each; there was one item forcing the subscale into two factors instead of fitting well with the rest of the items for both M[emot] and M[cog]. Therefore, ‘I am not very nostalgic when I listen to old songs (I used to listen to)’ was eliminated from M[emot], leaving four total items, and ‘I seldom like a song unless I admire the technique of the musicians’ was eliminated from M[cog], leaving four total items. While as remained somewhat lower than normal, possible reasons are discussed later. Cronbach’s a, M and SD for the three subscales are reported in Table 2.

Music in Everyday Life (North et al., 2004; Rana & North, 2007). Items about music usage andpreferences were adapted from North et al.’s (2004) ‘Uses of Music in Everyday Life’ survey. Participants rated on a five-point scale (1 = Never, 5 = Always) how often they listened to music with different people/groups of people (Listening Groups), to different music styles (Music Styles) and in different locations (Listening Locations). Several changes were made in the present study to make the survey age and culture appropriate; first, Spouse/partner was eliminated from the Listening Groups items. Second, on the Music Styles items, Blues and Country/folk were eliminated, ‘Golden oldies’ pop became Light/soft rock, and Non-Western pop and Non-Western traditional music became Kwaito and Traditional African, respectively. Finally, on the Listening Locations items, Driving and Pub/nightclub were eliminated, At home doing an intellectually demanding task became At home doing schoolwork, and Gym/exercising became Exercising/Playing sports. All three subscales were reduced using principal component analysis (see ‘Data reduction’ later).

Demographics. Participants completed a demographic questionnaire consisting of age, gender, race, language spoken at home, whom they live with, transportation method to school, and prior informal music experiences.

Procedure

All participants were recruited opportunistically by three of the authors of this study as part of a week-long service project that donated used band instruments to the schools. Data were collected over the course of two separate visits a year apart, with a music program started at each school in successive years. Testing took place in several large-group settings that were overseen by several experimenters and school teachers. Zulu-speaking teachers were available to answer any participant questions, and participants were instructed not to share answers with one another. All participants completed 12 pages of questionnaires consisting of demographics, Uses of Music inventory, Music in Everyday Life inventory, PANAS and several scales not analyzed here. Participants were given unlimited time to complete the surveys, and all participants completed the surveys in about an hour.

Results

Data reduction

The 12 items of the Music Styles, the 13 items of the Listening Locations, and the 7 items of the Listening Groups inventories were reduced through PCA and factors were extracted based on eigenvalues larger than 1 and the results of a scree test. Varimax rotation (varimax with Kaiser normalizations) was performed on the data to obtain a clear solution and maximize loadings.

Four underlying factors were extracted to account for 57.5% of the variance in the Music Styles inventory. Items loadings on the component matrix (with factor eigenvalues and individual variance explained) are reported in Table 1; as seen in the table, the factor structure was clear, with only a few cross-loading genres.

Two underlying factors were extracted on the Listening Locations inventory; the overall amount of variance accounted for was 31.5% (Religious Worship was excluded because it did not load onto either factor). Two underlying factors were also extracted on the Listening Groups inventory; the overall amount of variance accounted for was 52.6% (Family and On My Own were excluded because they did not load onto either factor).

Descriptive statistics

Descriptive statistics (a, M, SD and number of items) for all target measures are reported in Table 2. Participants’ ratings on both PA and NA were similar to previous results using the

Table 1. Factor loadings for music style preferences

|

Rock |

African |

Academic |

Party |

| Rock |

.84 |

|

|

|

| Alternative rock |

.83 |

|

|

|

| Light rock |

.67 |

|

|

|

| Traditional African |

|

.76 |

|

|

| Kwaito |

|

.71 |

|

.38 |

| Pop |

|

-.59 |

|

.43 |

| Rap |

|

-.46 |

|

.43 |

| Western jazz |

|

|

.80 |

|

| Western classical |

|

|

.79 |

|

| Light instrumental |

|

.35 |

.56 |

|

| Dance |

|

|

|

.68 |

| R&B/soul |

|

|

. |

.63 |

|

Eigenvalue = 2.22 |

Eigenvalue = 1.89 |

Eigenvalue = 1.52 |

Eigenvalue = 1.27 |

|

% Variance = 18.52 |

% Variance = 15.72 |

% Variance = 12.72 |

% Variance = 10.69 |

|

% overall variance explained = 57.55 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Note: Loadings < .30 have been omitted.

Extraction method: principal component analysis. Rotation method: varimax with Kaiser normalization.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics for target measures

|

α |

Number of Items |

M |

SD |

| Uses of Music |

| Background use (M[back]) |

.60 |

5 |

3.71 |

.81 |

| Emotional use (M[emot]) |

.34 |

4 |

3.82 |

.69 |

| Cognitive use (M[cog]) |

.26 |

4 |

3.40 |

.65 |

| Personality |

| PANAS positive (PA) |

.72 |

10 |

3.90 |

.57 |

| PANAS negative (NA) |

.73 |

10 |

2.14 |

.67 |

| Music Style Preferences |

| Rock |

.70 |

3 |

2.14 |

.96 |

| Academic |

.57 |

3 |

2.58 |

1.00 |

| African |

.56 |

4 |

3.19 |

.87 |

| Party |

.30 |

2 |

3.41 |

.66 |

| Music Usage |

| Listening Groups |

| With close others |

.36 |

3 |

2.62 |

.78 |

| With distant others |

.41 |

2 |

2.31 |

.88 |

| Listening Locations |

| Outside home |

.63 |

8 |

3.29 |

.67 |

| Inside home |

.48 |

4 |

3.87 |

.74 |

PANAS with a similar age-group of American participants (Lonigan et al., 1999; Lonigan, Richey & Phillips, 2002). Ratings on the three Uses of Music factors (reported as averages in this study) were multiplied by the number of items to compare to past descriptive statistics; all three subscales were similar to past reports that used Spanish and Malaysian participants (Chamorro-Premuzic, Gomà-i-Freixanet et al., 2009; Chamorro-Premuzic, Swami et al., 2009).

Inter-correlations and structural equation modeling

Table 3 reports the inter-correlations among the target measures of personality, uses of music, and music preferences and usage. Significant correlations (p < .05) were tested using SEM carried out via AMOS 5.0 (Arbuckle, 2003). The choice to use SEM was driven by two main reasons. First, unlike regression analyses, SEM enables one to simultaneously treat variables as predictors and criteria; second, SEM also enables one to model latent or unobserved factors from observed variables (Byrne, 2006). In the present study, we modeled a latent endogenous factor (‘styles’) to represent the common variance underlying preferences for the four different music styles (i.e., rock, party, academic and African), as well as a latent mediator (‘uses’), which represented the common variance underlying the three uses of music (i.e., background, cognitive and emotional). Modeling latent factors is a useful technique to simultaneously examine the role of general and specific factors in the model; for instance, if three observed variables are inter-correlated, removing the common variance among these variables enables one to examine the unique effects of each of the specific variables, that is, variability that is not shared by any other variable. In addition, we included PA and NA as exogenous factors (in line with past models examining individual difference factors as determinants of music uses and preferences).

Table 3. Inter-correlations among target measures

|

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

12 |

13 |

| 1. M[back] |

.18* |

.19** |

.28** |

-.04 |

.15* |

.13 |

.12 |

.15* |

.15* |

.03 |

.36** |

.43** |

| 2. M[emot] |

|

.29* |

.15* |

.19** |

.16* |

.18* |

-.17* |

.20** |

.13 |

.04 |

.40** |

.16 |

| 3. M[cog] |

|

|

.27** |

.04 |

.11 |

.22** |

.16* |

.04 |

.17* |

.09 |

.14* |

.07 |

| 4. PA |

|

|

|

-.06 |

-.02 |

.15* |

.00 |

.14 |

.10 |

.03 |

.28** |

.12 |

| 5. NA |

|

|

|

|

-.02 |

.10 |

.11 |

.04 |

.03 |

-.01 |

.01 |

.13 |

| 6. Rock |

|

|

|

|

|

.09 |

-.18* |

.18 |

.08 |

.03 |

.20** |

.09 |

| 7. Academic |

|

|

|

|

|

|

.03 |

.13 |

.18* |

.16* |

.16* |

-.02 |

| 8. African |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

-.21 |

-.11 |

.09 |

-.24** |

-.10 |

| 9. Party |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

.12 |

.14* |

.24** |

.17* |

| 10. With close others |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

.07 |

.41** |

.02 |

| 11. With distant others |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

.20* |

-.02 |

| 12. Outside home |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

.21** |

| 13. Inside home |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

.21** |

Note: N = 193; *p < .05, **p < .01; M[back] = background use of music, M[emot] = emotional use of music, M[cog] = cognitive use of music, PA = positive affect, NA = negative affect.

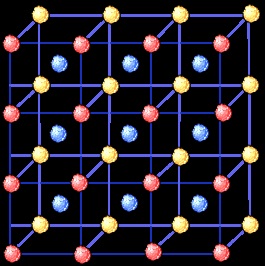

The following paths were hypothesized: from PA onto background and cognitive use of music, from NA onto emotional use of music, from cognitive use of music onto preference for academic music, and from the latent ‘uses’ factor onto the latent ‘styles’ factor. The hypothesized model did not fit the data well:1 c2 (N = 192, d.f. = 24) = 37.6, p < .05; GFI = .96, AGFI = .92; CFI = .87; PGFI = .51; RMSEA = .05 (.01–.09). In line with modification indices, two paths were added to the model in order to improve fit; namely, from PA onto the latent ‘uses’ factor, and from cognitive use of music onto preference for African music. The modified model (shown in Figure 1), explained the data well: c2 (N = 192, d.f. = 22) = 18.3, p > .05; GFI = .98, AGFI = .96; CFI = 1.00; PGFI = .48; RMSEA = .00 (.00–.05).

As seen in Figure 1, PA had a significant positive effect on cognitive use of music and background use of music, as well as an unpredicted positive effect on the latent ‘uses’ factor; NA had a significant positive effect on emotional use of music; cognitive use of music had a significant positive effect on preference for academic music and an unpredicted significant negative effect on preference for African music (since the loading of African music onto the latent ‘styles’ factor is negative, the effect of cognitive use of music on liking of African music also becomes a negative relationship); and, the latent ‘uses’ factor had a significant positive effect on the latent ‘styles’ factor.

Discussion

The current study examined the relationship between positive and negative affect, uses of music and music style preferences. Therefore, we sought to bring together two lines of past research, namely, extending uses of music research (Chamorro-Premuzic & Furnham, 2007) to a new culture and age-group, as well as combining this research with music preferences research (Rentfrow & Gosling, 2003, 2006). In addition, this study used PA and NA as predictors of uses of music. Since the PANAS is a standard and highly reliable measure of disposition.

Figure 1. Modified SEM model for affect, uses of music, and music preferences.

Note: *p < .05, ** p < .01; solid lines represent hypothesized paths, dotted lines represent modified paths; PA = positive affect, NA = negative affect, M(back) = background use of music, M(emot) = emotional use of music, M(cog) = cognitive use of music.

(Watson & Tellegen, 1985), it was predicted to correlate well (and in a similar manner as the Big Five) with music uses. This study was unique in its use of African and Southeast Asian adolescents from South Africa and its attempt to unify uses of music and music preferences research into a single model in which affect would predict music use, which in turn, would predict music preferences.

We found that, as predicted, PA positively correlated with background and cognitive use of music, while NA positively correlated with emotional use of music. The positive association between NA and use of music as emotional regulation can be explained in that individuals higher in neuroticism tend to experience a higher intensity of emotional affect, especially negative emotions (Costa & McCrae, 1992; DeNeve & Cooper, 1998). Past research has shown Extraversion to be consistently positively correlated with positive affect (DeNeve & Cooper, 1998; Lucas & Fujita, 2000); therefore, the link between PA and social or background use of music is consistent with previous findings. Finally, several PA scale items (i.e., Interested, Inspired, Determined, Attentive) have shown past links to openness (Mitte & Kämpfe, 2008), and therefore, the link between PA and intellectual uses of music is consistent with past findings.

In regards to music preferences research, the current study maps on well to previous findings by Rentfrow and Gosling (2003). In their analysis of undergraduates’ music preferences, four style factors were extracted: Reflective/Complex, Intense/Rebellious, Upbeat/Conventional and Energetic/Rhythmic. Our ‘Academic’ factor includes similar loadings to Reflective/Complex (i.e., western jazz, western classical), ‘Rock’ includes similar loadings to Intense/Rebellious (i.e., rock, alternative), and ‘Party’ includes similar loadings to Energetic/Rhythmic (i.e., R&B/soul, dance). ‘Traditional’ did not match previous style loadings because the genres (i.e., Kwaito, African) were unique to the South African population; however, Upbeat/Conventional (‘genres that emphasize positive emotions and are structurally simple’, 2003, p. 1241) still describe these genres. Obviously, there are numerous genres that were not explicitly tested in the present study; however, this study shows that the structure underlying music preferences identified by Rentfrow and Gosling (2003), if not the exact genres themselves, are able to be replicated across both age groups and cultures.

In the current SEM model, we did not predict any specific relationships between affect and musical style preferences; this is also in line with Rentfrow and Gosling (2003, 2006), who suggested that chronic emotional states (PA and NA) may not have a strong effect on music preferences, but rather, songs within each dimension can capture different emotional states. Therefore, the use of SEM allowed us to test whether uses of music are associated with affect, and in turn, whether uses in general are linked to higher preferences for all music styles. Indeed, not only were PA and NA related to the subscales of the Uses of Music inventory, but the latent ‘uses’ factor was significantly positively correlated with the latent ‘styles’ factor. While this general correlation between uses and preferences was found, we were not able to predict any specific correlations except cognitive use of music having a significant positive effect on preference for Academic music. Therefore, one direction for future research would be to examine the relationship between uses of music and music genre preferences more closely to establish how specific uses of music relate to preferences for specific genres.

Our results also included several measures of music usage: with whom (Listening Groups) and where (Listening Locations) participants listened to music (North et al., 2004). These factors were excluded from the final SEM analysis, in part because of lower than desired internal consistencies and in part to simplify the final model. Because these categories were developed for this study and not previously validated, we did not feel confident using these categories for further analysis. Although Cronbach’s alphas for emotional and cognitive uses of music were also lower than desired, these subscales have been used repeatedly in past research with consistently reliable results (Chamorro-Premuzic & Furnham, 2007; Chamorro-Premuzic, Gomà-i-Freixanet et al., 2009; Chamorro-Premuzic, Swami et al., 2009), and therefore were included in the present analysis. Although Listening Groups and Listening Locations were excluded from the final model, an interesting point exists in relation to these findings: more music usage factors showed significant correlations to background use of music (3 out of 4 significant) than emotional or cognitive uses of music (1 and 2 out of 4 significant, respectively). It may be that the music usage items and the factors extracted are more likely to lend themselves to a background use than other uses; for example, listening to music with close others and listening outside the home suggest an inherent background or social quality, whereas other items that showed weak loadings, such as listening by oneself or deliberately listening to music at home, would be more likely to correlate to emotional or cognitive uses of music. Future research should address this issue and produce a music usage scale that equally lends itself to background, cognitive and emotional functions of music.

A final note about the present results is in regards to the low Cronbach’s alphas for emotional and cognitive use of music. Because no previous studies of the Uses of Music Inventory have focused on adolescents, it may be that the social function of music overwhelms other uses for this age group. Previous research shows that adolescents use music for identity formation, socialization, and entertainment (Bakagiannis & Tarrant, 2006; North, & Hargreaves, 1999; North et al., 2000; Tarrant et al., 2000), but there has been less consistency in showing that adolescents use music for intellectual stimulation, which may be because of a lower capacity for musical analysis (Demorest & Serlin, 1997; Eerola et al, 2006; Krumhansl & Keil, 1982; North et al., 2000). If students are incapable of understanding music from a cognitive perspective, it makes sense that the internal consistency of the M[cog] items would be lower. Additionally, while much research exists to support an emotional use of music among adolescents (Juslin & Sloboba, 2001; Miranda & Claes, 2009; North et al., 2000; Saarikallio & Erkkilä, 2007; Saarikallio, 2008; Tarrant et al., 2000), the Uses of Music inventory does not distinguish between positive or negative mood regulation, which could cause lower internal consistency of results. In addition to a novel age group, a new cultural group was used as well. It is possible that since none of the participants had experienced formal music study before, the concept of music as an intellectual activity was foreign to them. Yet despite a lack of formal music education, the majority of participants in this study reported listening to music daily outside of school and owning a personal radio or music-playing device; so clearly, background use of music seems to be an important part of the South African culture. However, further research will need to be done to more fully examine the emotional and cognitive use of music both in South Africa and in the adolescent population.

Because of the novelty of the age and culture used in the present study, a number of limitations existed. First, the study relied only on self-reports of music use and preferences, which may not translate to actual music use and preferences in real life; this method only assumes that individuals accurately report on their uses and preferences for music. This limitation is compounded by the fact that participants completed the surveys in one sitting, and the results of this model are therefore only hypothetical and not verified across a longitudinal study. Further research could overcome this limitation by including actual music usage and preferences across a variety of settings for a more accurate depiction of uses of music and style preferences.

Second, although the present results were generally consistent with past research, it is important to note that we are using data from a non-western sample to support findings from western cultures. Although cross-cultural differences in the uses of music are likely to be minor (Rana & North, 2007; Chamorro-Premuzic, Swami et al., 2009), we cannot rule out that differences in the uses of music (for example, low internal consistencies) were the result of cross-cultural differences. The present findings also showed consistency to Rentfrow and Gosling’s (2003) music preferences categories; however, future research should examine the role of culture in uses of music and music preferences more thoroughly.

Finally, despite all efforts made to ensure the surveys were age and culture appropriate, it is still possible that participants did not have a complete understanding of the surveys. As previously mentioned, several of the surveys were adapted to make the items easier to understand, and Zulu-speaking teachers were available to answer participants’ questions. Of course, however, we have no guarantee that participants understood all of the items, and this could explain some of the differences found in the present study. On the other hand, multiple studies have shown that adolescents from African cultures were able to complete tasks and surveys with little difficulty (Eerola et al, 2006; Saarikallio, 2008). Additionally, extensive cross-cultural studies using participants unfamiliar to the psychological testing process have proven to be successful (Scherer, 1997a, 1997b; Scherer & Wallbott, 1994). It may still be beneficial for future research to address this issue by developing a Uses of Music inventory that is written in straightforward language with simple vocabulary that would be more appropriate for adolescents and non-native English speakers.

These limitations notwithstanding, the current study adds to the literature on both uses of music and music preferences, providing a link between these two bodies of music research. Indeed, the current study suggests that previous research on uses of music and music preferences does generalize across cultures and age groups, and also provides support for the growing literature suggesting that variations in music use and preferences are to some extent related to individual differences in temperament, particularly emotional dispositions.

Acknowledgements

The work of Laura Getz, Michael Roy, and Karendra Devroop on this project was supported by two Collaborative Interdisciplinary Scholarship Program Grants and a Professional Development Grant, all awarded by Elizabethtown College, USA. As part of these grants, concert band programs were initiated at two secondary schools in Pietermaritzburg, South Africa.

Notes

- The following fit indexes were used: c2 (Bollen, 1989), which tests whether an unconstrained model fits the covariance/correlation matrix as well as the given model (although non-significant c2 values indicate good fit, well-fitting models often have significant c2 values); the goodness-of-fit index (GFI) measures the percent of observed covariances explained by the covariances implied by the model; the AGFI adjusts for the degrees of freedom in the specified model; for both the GFI and AGFI (Hu & Bentler, 1999), values close to 1.00 are indicative of good fit; the CFI (Bentler, 1990) compares the hypothesized model with a model based on zero-correlations among all variables (values around .90 indicate very good fit); the parsimony goodness-of-fit indicator (PGFI; Mulaik et al., 1989) measures power and is optimal around .50; and for the root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA; Browne & Cuddeck, 1993), values < .08 indicate good fit.

References

Arbuckle, J. L. (2003). AMOS 5.0 Update to the AMOS user’s guide. Chicago, IL: Smallwaters.

Bakagiannis, S., & Tarrant, M. (2006). Can music bring people together? Effects of shared musical preference on intergroup bias in adolescence. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 47, 129–136.

Bentler, P. M. (1990). Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin, 107, 238–246.

Bollen, K. A. (1989). Structural equations with latent variables. New York: Wiley.

Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1993). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In K. A. Bollen & J. S. Long (Eds.), Testing structural equation models (pp. 136–162). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Byrne, B. M. (2006). Structural equation modeling with EQS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming (2nd ed.). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Cattell, R. B., & Anderson, J. C. (1953a). The measurement of personality and behavior disorders by the I.P.A.T. music preference test. Journal of Applied Psychology, 37, 446–454.

Cattell, R. B., & Anderson, J. C. (1953b). The I.P.A.T. Music Preference Test of Personality. Champaign, IL: Institute for Personality and Ability Testing.

Chamorro-Premuzic, T., & Furnham, A. (2005). Personality and intellectual competence. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Chamorro-Premuzic, T., & Furnham, A. (2007). Personality and music: Can traits explain how people use music in everyday life? British Journal of Psychology, 98, 175–185.

Chamorro-Premuzic, T., Gomà-i-Freixanet, M., Furnham, A., & Muro, A. (2009). Personality, self-estimated intelligence and uses of music: A Spanish replication and extension using structural equation modeling. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 3, 149–155.

Chamorro-Premuzic, T., Swami, V, Furnham, A., & Maakip, I. (2009). The Big Five personality traits and uses of music in everyday life: A replication in Malaysia using structural equation modeling. Journal of Individual Differences, 30, 20–27.

Christenson, P. G., & Roberts, D. F. (1998). It’s not only rock & roll: Popular music in the lives of adolescents. Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press.

Costa, P. T., Jr., & McCrae, R. R. (1980). Influence of extraversion and neuroticism on subjective well-being: Happy and unhappy people. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 38, 668–678.

Costa, P. T., Jr., & McCrae, R. R. (1992). NEO PI-R and NEO-FFI professional manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc.

Demorest, S. M., & Serlin, R. C. (1997). The integration of pitch and rhythm in musical judgment: Testing age-related trends in novice listeners. Journal of Research in Music Education, 45, 67–79.

DeNeve, K. M., & Cooper, H. (1998). The happy personality: A meta-analysis of 137 personality traits and subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 124, 197–229.

Eerola, T., Himberg, T., Toiviainen, P., & Louhivuori, J. (2006). Perceived complexity of western and African folk melodies by western and African listeners. Psychology of Music, 34, 341–375.

Eerola, T., Louhivuori, P., & Lebaka, E. (2009). Expectancy in Sami yoiks revisited: The role of data-driven and schema-driven knowledge in the formation of melodic expectations. Musicae Scientiae, 12, 231–272.

Eysenck, H. J., & Eysenck, M. W. (1985). Personality and individual differences: A natural science approach. New York: Plenum Press.

Gans, H. J. (1974). Popular culture and high culture: An analysis and evaluation of taste. New York: Basic Books.

Gregory, A. H., & Varney, N. (1996). Cross-cultural comparisons in the affective response to music. Psychology of Music, 24, 47–52.

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1–55.

IFPI. (2009, January). Digital Music Report 2009. Retrieved 20 October 20 2009, from http://www.ifpi.org/content/library/DMR2009. pdf

Juslin, P. N., & Laukka, P. (2003). Communication of emotions in vocal expression and music performance: Different channels, same code? Psychological Bulletin, 129, 770–814.

Juslin, P. N., & Laukka, P. (2004). Expression, perception, and induction of musical emotions: A review and a questionnaire study of everyday listening. Journal of New Music Research, 33, 217–238.

Juslin, P. N., & Sloboda, J. A. (2001). Music and emotion: Theory and research. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Krumhansl, C., & Keil, F. C. (1982). Acquisition of the hierarchy of tonal functions in music. Memory & Cognition, 10, 243–251.

Little, P., & Zuckerman, M. (1986). Sensation seeking and music preferences. Personality and Individual Differences, 7, 575–577.

Lonigan, C. J., Hooe, E. S., David, C. F., & Kistner, J. A. (1999). Positive and negative affectivity in children: Confirmatory factor analysis of a two-factor model and its relation to symptoms of anxiety and depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 67, 374–386.

Lonigan, C. J., Richey, J. A., & Phillips, B. P. (2002, November). Factor Structure of the Positive Affect Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) in a child, adolescent and young adult sample. Poster Paper presented at the annual convention of the Association for the Advancement of Behavior Therapy (AABT), Reno, NV.

Lucas, R. E., & Fujita, F. (2000). Factors influencing the relation between extraversion and pleasant affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79, 1039–1056.

McCown, W., Keiser, R., Mulhearn, S., & Williamson, D. (1997). The role of personality and gender in preferences for exaggerated bass in music. Personality and Individual Differences, 23, 543–547.

Miranda, D., & Claes, M. (2009). Music listening, coping, peer affiliation and depression in adolescence. Psychology of Music, 37, 215–233.

Mitte, K., & Kämpfe, N. (2008). Personality and the four faces of positive affect: A multitrait-multimethod analysis using self- and peer-report. Journal of Research in Personality, 42, 1370–1375.

Mulaik, S. A., James, L. R., van Alstine, J., Bennett, N., Lind, S., & Stilwell, C. D. (1989). Evaluation of goodness-of-fit indices for structural equation models. Psychological Bulletin, 105, 430–445.

North, A. C., & Hargreaves, D. J. (1999). Music and adolescent identity. Music Education Research, 1, 75–92.

North, A. C., Hargreaves, D. J., & Hargreaves, J. J. (2004). Uses of music in everyday life. Music Perception, 22, 41–77.

North, A. C., Hargreaves, D. J., & O’Neill, S. A. (2000). The importance of music to adolescents. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 70, 255–272.

Rana, S. A., & North, A. C. (2007). The role of music in everyday life among Pakistanis. Music Perception, 25, 59–73.

Rentfrow, P. J., & Gosling, S. D. (2003). The do re mi’s of everyday life: The structure and personality correlates of music preferences. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84, 1236–1256.

Rentfrow, P. J., & Gosling, S. D. (2006). Message in a ballad: The role of music preferences in interpersonal perception. Psychological Science, 17, 236–242.

Saarikallio, S. (2008). Cross-cultural investigation of adolescents’ use of music for mood regulation. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Music Perception and Cognition, August 25–29, 2008, Sapporo, Japan.

Saarikallio, S., & Erkkilä, J. (2007). The role of music in adolescents’ mood regulation. Psychology of Music, 35, 88–109.

Scherer, K. R. (1997a). Profiles of emotion-antecedent appraisal: Testing theoretical predictions across cultures. Cognition and Emotion, 11, 113–150.

Scherer, K. R. (1997b). The role of culture in emotion-antecedent appraisal. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 73, 902–922.

Scherer, K. R., & Wallbott, H. G. (1994). Evidence for universality and cultural variation of differential emotion response patterning. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 66, 310–328.

Schmukle, S. C., Egloff, B., & Burns, L. R. (2002). The relationship between positive and negative affect in the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule. Journal of Research in Personality, 36, 463–475.

Schwartz, K. D., & Fouts, G. T. (2003). Music preferences, personality style, and developmental issues of adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 32, 205–213.

Soto, C. J., John, C. P., Gosling, S. D., & Potter, J. (2008). The developmental psychometrics of Big Five self-reports: Acquiescence, factor structure, coherence, and differentiation from ages 10 to 20. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 94, 718–737.

Tarrant, M., North, A. C., & Hargreaves, D. J. (2000). English and American adolescents’ reasons for listening to music. Psychology of Music, 28, 166–173.

Tekman, H. G., & Hortaçsu, N. (2002). Music and social identity: Stylistic identification as a response to musical style. International Journal of Psychology, 37, 277–285.

Watson, D., & Clark, L. A. (1984). Negative affectivity: The disposition to experience aversive emotional states. Psychological Bulletin, 96, 465–490.

Watson, D., & Tellegen, A. (1985). Toward a consensual structure of mood. Psychological Bulletin, 98, 219–235.

Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS Scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 47, 1063–1070.

Zillmann, D., & Gan, S. (1997). Musical taste in adolescence. In D. J. Hargreaves & A. C. North (Eds.), The social psychology of music (pp. 161–187). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Acknowledgements

The work of Laura Getz, Michael Roy, and Karendra Devroop on this project was supported by two Collaborative Interdisciplinary Scholarship Program Grants and a Professional Development Grant, all awarded by Elizabethtown College, USA. As part of these grants, concert band programs were initiated at two secondary schools in Pietermaritzburg, South Africa.

Biographies

Laura M. Getz is a first-year Cognitive Psychology graduate student at the University of Virginia, USA. The data presented here were collected while she was an undergraduate at Elizabethtown College and analyzed while working in collaboration with Dr Chamorro-Premuzic at Goldsmiths, University of London, UK. Her research interests include the combination of music and psychology, both from a personality and cognitive perspective.

Tomas Chamorro-Premuzic is a world-wide expert in personality, intelligence, human performance, and psychometrics. He is a Reader at Goldsmiths, Research Fellow at UCL, and Visiting Professor at NYU in London.

Dr Chamorro-Premuzic has published more than 100 scientific articles and 5 books, covering a wide range of social and applied topics, such as human intelligence and genius, consumer and media preferences, educational achievement, musical preferences, creativity and leadership, and he frequently appears in the media to provide psychological expertise to a wide audience. His current interests include online dating, employability, film preferences, and entrepreneurship.

Michael M. Roy is an Assistant Professor of Psychology at Elizabethtown College, USA. The majority of his research is in the area of social cognition. In addition, he is a drummer and has been an active performer for a number of years.

Karendra Devroop is Associate Professor of Music and Director of the School of Music and Conservatory at North West University in Potchefstroom, South Africa. His major research area is the occupational development of professional and amateur musicians.

Note* This is reprint article . It has been published earlier at

http://pom.sagepub.com/

http://pom.sagepub.com/content/40/2/164

Published by: http://www.sagepublications.com